Nashville handoff from CoreCivic is a turning point for reform efforts, but not an end – The Tennessean

| Nashville Tennessean

At 6 a.m. Sunday, staff at the Metro-Davidson County Detention Facility will arrive in tan uniforms for the first time to be sworn in as the newest employees of the Nashville sheriff’s office.

The planned ceremony represents a turning point for the facility.

For progressive Metro Council members, it is a long-sought victory, the result of years of lobbying to shift the facility into government control after decades under the private prison giant CoreCivic.

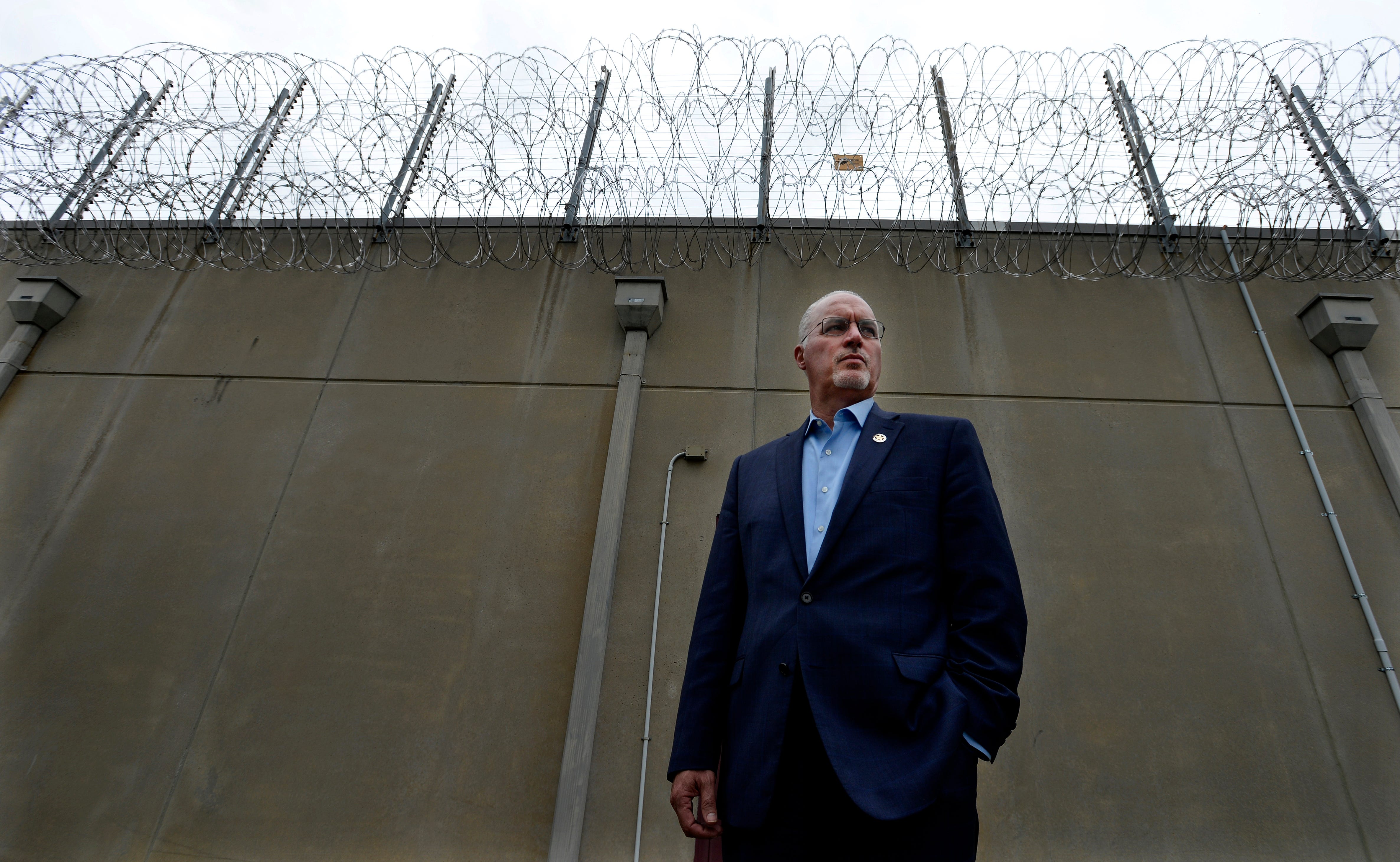

For Nashville Sheriff Daron Hall, it is the culmination of a fast-paced takeover that started abruptly after CoreCivic walked away from its agreement with the city this summer.

For activists pushing the city to pursue ambitious criminal justice reforms — at jails, in courtrooms and within the police department — it is just the beginning. They say simply turning the keys over to Hall’s team will do little to address the central problems with incarceration and life behind bars.

A corrections expert says bringing the facility under public control will increase transparency and give activists a better opportunity to scrutinize policies and conditions there.

Reform advocates are not taking a victory lap because they say systemic change in the criminal justice system will take bolder action.

“We really need to do all that we can to improve the way that we charge and incarcerate mostly Black and brown people,” said Council member Emily Benedict, who earlier this year championed legislation to sever ties with CoreCivic.

“There’s a lot of things to be looked at,” Benedict said. “This happens to be one, and it might not even be the biggest one. We have to look at these things as incremental steps.”

Sheriff doesn’t expect operations to change much under his leadership

The transition at the Metro-Davidson County Detention Facility follows a contentious battle between activists, politicians and business leaders.

This summer, Benedict and Council member Freddie O’Connell revived plans to take over the detention center. They proposed a two-year transition timeline.

But CoreCivic, which was in the middle of negotiating a five-year contract with the city, announced it would act much more quickly, turning the facility over to the sheriff Oct. 4.

RELATED: CoreCivic accuses Nashville of ‘playing politics,’ will walk away from prison contract with city

“Once clear that the parties we were negotiating in good faith with on the long-term contract were also furtively working to end the relationship with CoreCivic, it became clear it was time to go ahead and transition the management of (the facility),” CoreCivic spokesperson Steven Owen said in a statement.

The company’s surprise exit gave Hall two months to get ready, all while he was overseeing the opening of a new downtown jail and the pernicious impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In an interview days before he was set to take over the Nashville facility, Hall said the work had consumed his team for weeks, but he was ready to take the reins.

Hall said it will take $2 million to bring sheriff’s office services to the facility. That money will go toward equipment, training and other immediate needs.

About 123 of the current facility employees will transfer to the sheriff’s office. Final staffing levels and day-to-day operating expenses are still unknown.

The state seemed open to negotiating reimbursement to accommodate those day-to-day costs and the $2 million startup costs, Hall said. But it will be months before officials know for sure if the city will be on the hook for any of that extra money.

“We can operate the facility short term,” Hall said. “I think long term, we all as a city in the state sit down and figure out what is the best thing to do on this site?”

Despite the impassioned calls from activists and council members, Hall isn’t convinced the change from CoreCivic to the sheriff’s office will mean much inside the facility.

“I always thought this was overstated,” he said. “On the ground in here, these are people doing the same work we’re doing.”

Hall said his team never saw significant problems while overseeing the contract with CoreCivic, and he cast the transition as more of a “philosophical change” than a performance-based issue.

“I do believe there is some public accountability,” Hall said, adding that government offices are generally more transparent. “I think that’s real. I think that’s fair.”

Criminal justice professor Miriam Northcutt Bohmert, who teaches at Indiana University, agreed. She said private prison companies generally share less information about conditions and policies within their facilities.

Unlike public facilities, which fall under elected officials, it can be hard to pin down who is responsible for conditions inside, Bohmert said.

“Who do I contact if I’m angry about a private prison, and what leverage do I have over them?” she said. “It just gets a lot trickier.”

Owen, the CoreCivic spokesman, said the company complies with all open records and is “treated as the functional equivalent of government.” He said complaints could be submitted via a hotline and conditions in facilities were examined regularly through audits.

Activists already pushing city to go further

Activists seem poised to use the public takeover as a launching pad to push Hall and city leaders toward more aggressive reforms.

A September report released by a coalition of community groups said Hall should close down the facility, which currently houses about 474 inmates. They want Hall to focus on shrinking jail rosters citywide.

“Our community needs an expansion of health care. We need low income housing. We need greater educational opportunities. We need fresh, healthy and affordable food,” the coalition, which includes Black Lives Matter Nashville and Gideon’s Army, said in its report.

“Metro Nashville Government, we are asking you to take bold action. We demand converting the use of Metro Detention Facility from a jail to something that will actually make our community safe and continue the trend of decarceration.”

The transition came fast after years of effort

CoreCivic, among the largest for-profit prison company in the country, has long been battered by criticism that officials skimp on health care, reentry training and other programming to increase profits.

Activists urged governments and banks to cut ties with the private prison company. Oversight and accountability would improve, they said, if prisons and jails were run by governments subject to public records laws and voters.

CoreCivic has pushed back against criticism, calling it misleading and based in ideology rather than facts.

The Nashville area, which is home to CoreCivic’s corporate headquarters, became an epicenter of that fight. In 2018, dozens of protesters blocked the company’s corporate office in Nashville, ultimately resulting in a smattering of arrests.

Critics said a 2017 outbreak of scabies at the CoreCivic-run Nashville detention facility, and allegations of a cover-up, were emblematic of problems within private prisons.

A lawsuit filed by employees at the jail alleged they faced retaliation if they spoke out about the problem. That echoed a lawsuit from inmates who claimed they would be placed in solitary confinement if they discussed scabies. CoreCivic said they notified the city and sheriff’s office “from the start.”

The scabies outbreak amplified calls for the Nashville government to take over the local facility, which houses inmates serving short state sentences.

CoreCivic operated the 1,300-bed detention center since it opened in 1992. The cost of the company’s contract with the city is covered by the Tennessee Department of Correction because those inmates would otherwise go to state prisons.

After details of the scabies outbreak came to light, O’Connell sought to strengthen oversight at the facility. He asked Sheriff Daron Hall to examine the potential cost of breaking with CoreCivic and moving the facility under the sheriff’s office.

“Unfortunately, we’ve learned enough about both mass incarceration and private management of prisons to suggest that this is not an ideal component of our criminal justice system,” O’Connell said in September 2019.

Then, earlier this year, Hall handed over a report suggesting he could take over the detention facility without incurring a mountain of extra costs. Hall said state officials agreed to renegotiate the reimbursement rate at the facility to cover higher costs he he would need for employee pay and benefits.

The report renewed the Nashville council’s interest in taking over the detention center. As that effort gained momentum, CoreCivic stepped aside.

Now, activists see an opening to pursue an ambitious end goal.

“Nashville is better, safer and healthier when we decarcerate and reallocate funds away from cages and back into our community,” the activists’ September report read. “We have an opportunity to do something truly great and truly restorative.”

Reach Adam Tamburin at 615-726-5986 and atamburin@tennessean.com. Follow him on Twitter @tamburintweets.