COVID-19 Shut Down America’s Sports. Will Music Be Next? – Forbes

It’s a little before midnight on Thursday, March 12th. Trey Wilson is hunched over his desk in his Nashville home office. He’s already been working since 7:00 am.

1600 miles away backstage at Ottawa’s Bronson Centre amphitheater, five guys with long hair, thick beards, and flashy Ray-Bans have just finished up a show in front of a sold-out crowd. The band—a bluesy, southern rock ensemble called Blackberry Smoke—is midstream in a ten-day, eight venue cross-Canadian trip that has been years in the making to kick off the first leg of their 2020 North American tour.

Blackberry Smoke.

David McClister Photography

As the band noshes on vegetable lasagna and coconut La Croix, Wilson, the band’s manager, is flipping through Blackberry Smoke’s social media channels on his phone. Fans are blowing them up.

“Are the shows still on?”, asks one from Toronto. “Hope you’re coming to Vancouver! Can’t wait to see you guys!”, proclaims another. The posts keep coming one after another, by the hundreds. Simultaneously, Wilson’s emailing furiously with Denise Ross, Vice President of Live Nation Canada.

“Hear anything about border crossings?” Wilson asks. “I don’t know if we will make it past Toronto. Guys in the band are wondering.”

“Haven’t heard anything about border crossings, no,” Ross fires back. “I’m about to go into a meeting. Can I call you in 30?”

“Please do,” Wilson responds, “Everyone is getting concerned.”

Seconds later, Wilson’s two young boys, ages 2 and 3, show up at his home office door, restless and unable to sleep.

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 13 : President Donald J. Trump speaks with members of the coronavirus task … [+] force during a briefing in response to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic in the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room at the White House on Monday, April 13, 2020 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The Washington Post via Getty Images

Twenty-four hours earlier, the World Health Organization officially declared Covid-19 a global pandemic. That same day, President Trump shut down all travel between the U.S. and 26 EU countries in a televised prime time address, amounting to the largest international travel ban since World War II.

What was certain that night, Wilson recalls, was that coronavirus was the real deal. What no one knew was whether the U.S.-Canadian border would be next to shut down, trapping the band in an international no man’s land as coronavirus surged.

Early the next morning, Blackberry Smoke’s caravan pulled into Kitchner, Ontario for the tour’s third show. Not long after they arrived, word leaked out that Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was preparing to close the airports. Live Nation’s Ross pinged Wilson minutes later.

“We don’t have time to wait. I’m sorry,” Ross wrote, “We MUST announce the postponement of the Ontario shows NOW.” At the time, most of Canada’s provinces were within hours of locking down.

Wilson didn’t hesitate. He texted the band from Nashville, “PACK YOUR BAGS”, and began scouring Google maps for every nearby airport. Three hours later, Blackberry Smoke boarded the last flight out of Toronto back to the U.S., the rest of their North American tour now officially “TBA” (to be announced).

PORTLAND, OREGON – FEBRUARY 01: Rudy Gobert #27 of the Utah Jazz reacts in the fourth quarter … [+] against the Portland Trail Blazers during their game at Moda Center on February 01, 2020 in Portland, Oregon. NOTE TO USER: User expressly acknowledges and agrees that, by downloading and or using this photograph, User is consenting to the terms and conditions of the Getty Images License Agreement. (Photo by Abbie Parr/Getty Images)

Getty Images

In some way, it all started with Rudy Gobert.

Within hours of news breaking that the Utah Jazz All-Star center had tested positive for coronavirus on March 11th, panic swept across the NBA. Among major professional sports, none involves more direct, constant physical skin-to-skin contact than basketball. If Gobert had tested positive, how many others were infected as well? Contact tracing quickly revealed that Gobert potentially could have spread the virus to hundreds of other players, coaches, support staff, and reporters.

Later that same night, the NBA put its season on ice.

President Trump’s Coronavirus guidelines and news headlines, Pandemic 2020. (Photo by: Jeffrey … [+] Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The magnitude of the NBA’s Board of Governors’ decision took seconds to reverberate across America, confirming many people’s worst fears about how fast coronavirus was spreading undetected, and solidifying the sober reality of its lethality in anyone who previously had mocked it—including Gobert. If NBA titans with personal physicians like Gobert, LeBron James, and Kevin Durant were at risk, what about the rest of us?

The fallout from Gobert’s diagnosis just cratered deeper from there. The realization that one of America’s most profitable sports leagues, worth billions in revenue annually, could simply be suspended overnight sent the initial seismic shudder through the stock markets. It was the first sign for many on Wall Street that coronavirus could trigger a cascading financial crisis. How would the economy function if people couldn’t congregate face to face—at sporting events, casinos, hotels, restaurants, bars, conferences, and at work? Who’s next?

Traders work during the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on March 18, 2020 at Wall … [+] Street in New York City. – Wall Street stocks plunged again March 18, 2020 as the economic toll from the coronavirus mounts and economists warn of a deep recession. The Dow Jones Industrial Average tumbled 6.3 percent, or more than 1,300 points, to close the day at 19,903.50. The index sank by as much as 10 percent earlier in the session, which saw trading halted yet again. (Photo by Johannes EISELE / AFP) (Photo by JOHANNES EISELE/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images

Tennis was next. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) suspended all men’s tournaments early the following morning. Major League Soccer (MLS), the National Hockey League (NHL), Formula 1, NASCAR, and the PGA closed up shop hours later. By the end of the day, after briefly toying with the prospect of playing games in empty arenas without fans, the NCAA cancelled March Madness entirely.

Over the next two weeks, like the stock market free fall it would subsequently trigger, every major sporting event and league in America—and around the world—was either suspended, postponed, or cancelled outright, including Major League Baseball’s Opening Day, one of America’s most iconic sporting traditions. Nothing was spared. Not even badminton. When the International Olympic Committee postponed the 2020 Summer Games for a year on March 23rd, that pretty much put the nail in the world’s sporting coffin.

LONDON, ENGLAND – JULY 14: Roger Federer of Switzerland in action during the Men’s Singles Final … [+] against Novak Djokovic of Serbia ( not pictured) at The Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Championship at the All England Lawn and Tennis Club at Wimbledon on July 14, 2019 in London, England. (Photo by Simon Bruty/Anychance/Getty Images)

Getty Images

The financial losses from Covid-19’s attack on sports are staggering to comprehend.

Wimbledon, one of tennis’s four Grand Slams that takes place in late June, rakes in $1 billion over two weeks every year. It was officially cancelled on April 1 for the first time since World War II. The Tour de France, which aspirationally has been postponed until late August, nets billions for riders, teams, advertisers, sponsors, television networks, and the French economy. The cumulative, interconnected losses from the evaporation of professional sports globally through the rest of 2020 would take a Goldman Sachs to unwind, though estimates from a prolonged shut down of just three of America’s four major professional sport leagues (MLB, NBA, NHL) excluding the NFL through June alone is estimated at over $10 billion.

Then there’s the employment toll. Sports leagues are massive American job generators, from athletes’ security detail, agents, PR, and handlers down to the stadium concession workers, parking attendants, bus drivers, caterers, and maintenance contractors. Hundreds of thousands of these people are now temporarily furloughed or have been laid off permanently.

In an April 14th Rose Garden speech on re-opening the American economy, President Trump declared that, “We have to get our sports back.” He was speaking both economically and emotionally. Sports inspire us, motivate us, and remind us of the fundamental meaning of team. Regardless of politics, no one likely disagrees with him.

But what about music? When America’s stadiums and arenas aren’t packed with sports’ fanatics, they’re crammed with millions of twirling, dancing, air guitar playing, merchandise-buying music fans who fill in the vital economic gaps between major league sports seasons.

Coronavirus has brought American sports to a standstill. Is music next?

Coronavirus shut down America’s sports. How long before live music is next?

Courtesy of Blackberry Smoke

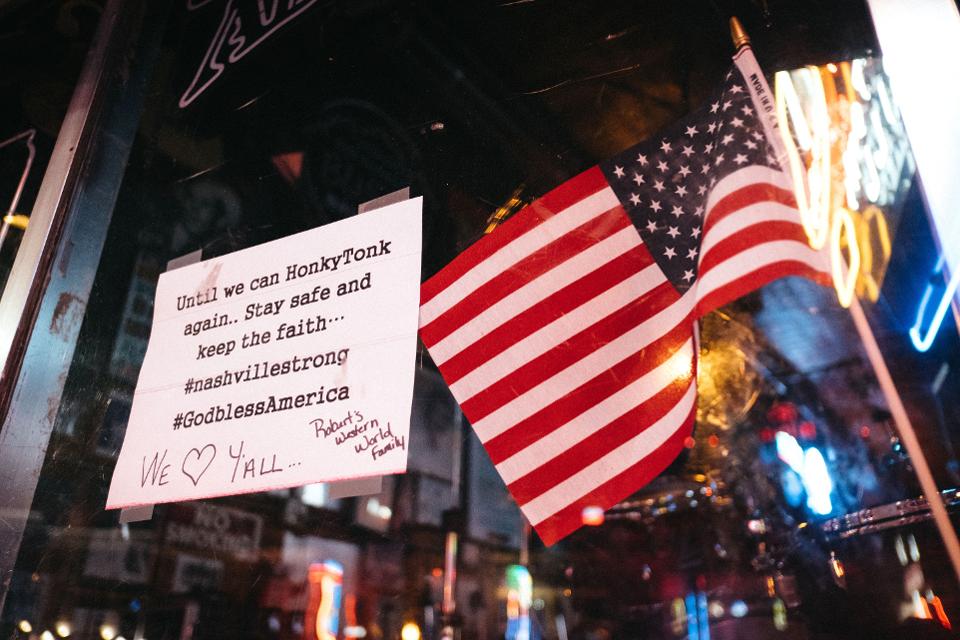

On Sunday March 15th, two days after Blackberry Smoke landed back in the U.S., Mayor John Cooper shut down Nashville’s bars and restaurants, including the world-famous honkytonk mile on lower Broadway that has birthed dozens of country music legends and is the epicenter of the city’s tourism.

The following Sunday, as positive coronavirus cases began to surge, Cooper issued a county-wide stay-at-home order, effectively putting Nashville’s entire music scene—musicians, managers, agents, writers, sound engineers, record executives, concert promoters, caterers, roadies, riggers, gaffers, and grips—on lock down. In less than a week, America’s Music City went silent.

NASHVILLE, TN – APRIL 08: A sign is posted in Downtown Broadway is seen at night on April 8, 2020 in … [+] Nashville, Tennessee. All establishments have been closed due to the coronavirus (COVID-19). (Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Getty Images

“It was surreal,” recalls Ken Levitan, founder of Vector Management and an industry legend who’s managed the likes of Kings of Leon, Emmylou Harris, the late Kenny Rogers, and Hank Williams Jr. “Everything about music is about people coming together face to face—writing it, recording it, promoting it, getting out on the road to play it in front of fans. No one could really fathom that the entire industry could shut down overnight. They still can’t.”

Levitan closed his Music Row office on March 13th, and sent everyone packing to work from home. As nationwide infections began doubling, his typical bi-weekly calls with artists, agents, and concert promoters rapidly morphed into hourly triage. Older, established artists with already compromised immunities were concerned about touring and getting sick. Younger, up-and-coming musicians with far less margin for financial error worried what would happen if they couldn’t tour and if they’d have to lay people off.

When music’s “Cancellation Apocalypse” finally descended that week, it hit Nashville like a fast-moving tsunami.

“For me, it all started with Alison Krauss,” Levitan recalls. “She was really paying attention to what was happening starting back in February. And she was the first one to pull the plug on her tour. It all cascaded from there. For music, sports are kind of a canary in the coal mine, since we all play in the same places and our industries are both based on large crowds. After sports shut down, a lot of us knew it was only a matter of time for the next shoe to fall.”

ISTANBUL, TURKEY – MARCH 15: General view of the Turk Telekom Stadium ahead of the Turkish Super Lig … [+] week 26 football match between Galatasaray and Besiktas, to be played behind closed doors over coronavirus (Covid-19) concerns on March 15, 2020. (Photo by Muhammed Enes Yildirim/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

For Levitan, Hank Williams Jr. fell next. Followed by Lynyrd Skynyrd, John Hiatt and Peter Frampton. By the end of March, Vector had postponed or cancelled all of its 2020 tours through September. Up and down Music Row, an unassuming strip of brightly-painted, historic homes where Nashville’s powerbrokers concentrate, the same scene was playing out in every other office: frantic conference calls with concert promoters and record executives, rapid fire decisions based on constantly evolving information, artists panicking about what to do in the meantime, and no one knowing what happens next.

“The music industry has been through a lot before,” Levitan recalls of those last two weeks of March. “We’re used to shocks. There was Napster. The death of records and CDs. September 11th. But this was completely uncharted territory. It still is.”

Ken Levitan (right) on stage with Lynyrd Skynyrd in Canada

Courtesy of Vector Management

STADIUM AREA, NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE, UNITED STATES – 2017/07/17: Nashville city skyline at dusk. … [+] (Photo by John Greim/LightRocket via Getty Images)

LightRocket via Getty Images

Music City’s lockdown didn’t sink in at first—mostly because no one really believed the industry’s silencing would persist. Mayor Cooper’s initial stay-at-home order lasted only two weeks. It was also professionally unimaginable that anything, including a pandemic virus, could shut music down.

“Everyone was just kind of numb at first,” recalls Wilson. “People here are programmed to tour, play live, and engage with fans face-to-face, regardless of where they fit into the music scene. It’s what people here love and how they put food on their tables. Not touring or cancelling shows just isn’t in this town’s DNA.”

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE – OCTOBER 22: Joe Bonsall, Duane Allen, William Lee Golden and Richard Sterban … [+] of The Oak Ridge Boys perform at the Grand Ole Opry House on October 22, 2019 in Nashville, Tennessee. (Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Getty Images

On March 30th, Governor Bill Lee finally locked Tennessee down, joining 28 other states in shuttering all non-essential businesses and restricting residents’ movements. That same day, Mayor Cooper extended Nashville’s stay-at-home order through the rest of April. 900 miles northeast in New York City, coronavirus infections were surging past 38,000. More than 1,000 people were already dead.

More broadly, America’s healthcare system, some of whose largest players like HCA Healthcare and LifePoint Health are Nashville-based, was being exposed for being woefully underprepared for a pandemic—undersupplied with PPE (personal protective equipment), ICU beds, critically needed ventilators, and rapid testing capabilities.

For Nashville’s music industry, this was the moment it all began to hit home: coronavirus’s curve wasn’t going to flatten, and nothing was returning to “normal”, any time soon.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – DECEMBER 13: Taylor Swift performs during the 2019 Z100 Jingle Ball at Madison … [+] Square Garden on December 13, 2019 in New York City. (Photo by Taylor Hill/FilmMagic)

FilmMagic

“The industry-wide realization that Covid-19 could affect touring and live events for longer than just a month or two took a while to get real,” publicist Janet Edbrooke of Essential Broadcast Media tells me. EB Media represents top touring artists like Kenny Chesney, Eric Church, George Strait, and Darius Rucker (formerly Hootie of the Blowfish kind). “Then in late March it really hit home for the artists and their teams who are so dependent on touring income that this wasn’t going away. This was real. This was long-term.”

The evisceration of American sports has been widely covered by the media (and Trump). Far fewer people, however, know how deep and wide music’s carnage runs, and what it means for the economy. As of this past week, most of music’s highest grossing tours and festivals have been either postponed or cancelled for 2020 including: Taylor Swift (April 17th), Justin Bieber (April 1), Rolling Stones (March 17th), Camila Cabello (March 24th), Kelly Clarkson (March 13th), Jonas Brothers (March 14th), Alicia Keys (March 20th), Mariah Carey (March 4th), Zac Brown Band (March 20th). Shania Twain (April 11th). The list goes painfully on.

In Music City, no one I spoke with has yet had the stomach to do the collective financial math. Many still don’t want to acknowledge that coronavirus’s lasting impacts may not have even begun to peak yet. But the immediate downstream impacts of the pandemic on Nashville’s economy, unemployment, and tourism scene are becoming clearer every day as the industry comes to grips with what music’s “new normal” might look like.

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE – MARCH 11: Scotty McCreery performs onstage at Ryman Auditorium on March 11, … [+] 2020 in Nashville, Tennessee. (Photo by John Shearer/Getty Images for Scotty McCreery)

Getty Images for Scotty McCreery

“I think we’re only just beginning to comprehend the long-term impacts,” Sarah Trahern, CEO of the Country Music Association, tells me. “Music in Nashville alone generates over $12 billion annually, incorporating businesses from labels and recording entities to publishers, production and touring companies, venues, radio, advertisers, and more. In less than a month, more than 40,000 music industry professionals have been impacted, either through decreases in pay, getting furloughed, or losing their jobs altogether. It’s too soon to know the extent of the long-term impacts. But it will be substantial, especially in the sectors that are dependent on touring revenue. Nashvillians are resilient, but my heart breaks for our town right now. Everyone is hurting.”

Bands and musicians, particularly those that tour frequently, are no different than any other small business. Vector’s Levitan likens them to restaurants or independent retailers: their success is built on a loyal fan base of ‘regulars’, operations and presentation are everything, consistency is king, reviews can make or break you, and no one can afford an off-night if you want to last.

More critically, the majority of musicians don’t have a Kenny Chesney or Lady Gaga-sized nest egg to fall back on. At any given time, most artists are a few months away from insolvency.

“75% of restaurants probably won’t be here after this is all said and done,” Levitan tells me, “The pandemic will re-order everything for music as well depending on how long it lasts and how the future is re-negotiated. Touring acts can’t afford not to tour. But if venues and festivals start asking for 20%-30% cuts in what an act charges, that’s all of the profits. There’s nothing left. It’s scary enough right now to think about touring when you might be putting your health at risk. So why would any artist take on that risk, and put their crew and their families at risk, without making money and putting food on the table? There will have to be lots of adjustments.”

For the hundreds of thousands of men and women across the country who keep music humming in the trenches, but don’t get the headlining credit, the scope and scale of the industry’s coronavirus shutdown makes an already devastating reality even worse.

“Artists who tour on a major level are laying off their extended family,” laments CMA’s Trahern, “And it’s not just the immediate touring family. It’s every part of their business funnel, from merchandisers to production to caterers to staging teams. The financial fallout is already massive.”

“Firing people is one of the hardest things anyone has to do,” adds Levitan. “It’s even harder for artists and bands when these people been with you for years and they have no other place to go right now.”

Ken Levitan with his legendary client the late Kenny Rogers

Courtesy of Vector Management

While no one’s been left unscathed from the pandemic, it’s been particularly devastating on younger, up-and-coming artists.

“With smaller musicians and bands, the impact of (coronavirus) is being felt even harder,” says Trahern, “Not only just financially, but mentally and emotionally as well. Can you imagine what it feels like for a new musician to ride an initial wave of amazing momentum only to have it halted due to this pandemic?”

Covid-19’s bludgeoning of the summer music festival circuit has doubled that gut punch. Music festivals are like scouting combines: they give emerging talent the chance to expose themselves to established stars and agents, and an opportunity make an early name for themselves. It now looks like 2020 won’t be anyone’s breakout year. Most of the online festival calendars for summer are now papered with “CANCELLED” or “POSTPONED”.

The festival pain is even more acute for the small towns and cities that host them. In many of these off-circuit places—like Tillmon, TX, Florence, AZ, Pryor, OK, Walker, MN, and Forest City, IA—music festivals are like Christmas retail, accounting for a large portion of annual tourism revenue and sustaining the small business ecosystem by filling up hotels, restaurants, bars, retailers, campgrounds, and short-term rentals.

Music’s annual awards shows are Covid-19’s other deep casualty, including the Academy of Country Music Awards, the Billboard Music Awards, and the iHeartRadio Awards, depriving artists, like Olympic athletes, of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be publicly recognized for their talents and contributions.

NASHVILLE, TN – APRIL 08: The Ryman Auditorium is seen at night on April 8, 2020 in Nashville, … [+] Tennessee. All establishments have been closed due to the coronavirus (COVID-19). (Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Amid the layoffs, cancellations, doom, and gloom, however, there are bright spots of opportunity and kindness.

Nashville has rallied around itself, as is its instinct, initiating dozens of fundraisers to support the people who have been furloughed or laid off, as well as supporting programs to keep emerging artists in the game, including MusiCares’ Covid-19 Relief Fund sponsored by the Grammy Recording Academy, the Academy of Country Music’s Lifting Lives Covid-19 Response Fund, and the Music Health Alliance, which provides musicians and others in the industry with financial and healthcare assistance.

Artists are also digging new opportunities from Covid-19’s adversity. Trapped at home, fans have never craved content more. Music streaming is booming, up 19% recently, and hundreds of bands and musicians are engaging new platforms to stay connected with followers, including Instagram concerts, spontaneous YouTube videos, and virtual online shows from impromptu, at-home studios. Many artists also aren’t backing off from releasing new music that was already in the pipeline pre-corona—sensing a unique moment to build new audiences.

Drake White

Courtest of Rev. White Records

“For a lot us whose main source of income is touring, we have to find other means to support our families and keep this town alive right now,” says Drake White, a Jack Johnson-meets-Joe Cocker-stage-master who’s releasing a new EP this week under his own label Rev. White Records. “As musicians and artists we’re all just trying to innovate, write, and create content that keeps fans engaged. I’m personally trying to use this down time as a muse, to tap into different creative outlets. I think releasing music is a must right now because people need something to listen to first and foremost, but I also believe they need something to grab onto spiritually now more than ever.”

Levitan’s artists aren’t sitting idle either. Many of them are taking the forced time off from touring and non-stop press schedules to get back to their original craft and make new music virtually while maintaining social distancing guidelines.

“We’ve had several artists cut new tracks over the past few weeks with everyone in a different studio,” Levitan tells me. “Sometimes they’re hundreds of miles away in different time zones. Song writers are collaborating by video chat. But it all sounds amazing—like they were literally in the same studio. What’s happening right now is pushing the boundaries of technology. We’ve always been an industry that’s capable of adapting quickly, and this pandemic could ultimately be transformative in how we look at making music moving forward in the future.”

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA – MARCH 10: LeBron James #23 of the Los Angeles Lakers grabs a rebound in … [+] front of Anthony Davis #3 during a 104-102 loss to the Brooklyn Nets at Staples Center on March 10, 2020 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Harry How/Getty Images) NOTE TO USER: User expressly acknowledges and agrees that, by downloading and or using this photograph, User is consenting to the terms and conditions of the Getty Images License Agreement.

Getty Images

But what, exactly, does that ‘future’ look like?

On April 15th, President Trump held a conference call with the Commissioners of America’s major sports leagues including the NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL, and the PGA, focusing on when—and how—to re-open the country to sports. Two days later at his daily briefing, Trump outlined how that could happen.

“Sports are coming back,” Trump said from the podium. “At first, they’ll probably be made for TV. Like the good old days. Then, when the time is right, we’ll start bringing back the fans and filling up the stadiums. Maybe there’ll be two or three seats between people. Maybe people will be wearing masks. We don’t know at this point. But sports will be coming back I can guarantee you that. And they’ll be coming back soon.”

Notably missing from the President’s remarks was how to re-fill America’s stadiums and arenas with music fans, and what that will look like when it happens.

No one I spoke with in Music City professes to know. There’s still too much uncertainty around flattening the curve and the potential for the virus to re-emerge this fall, even if current stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures are effective. But everyone in Music City agrees on this: it’s not about the artists, the labels, the promoters, the agents, or the crews. It’s about the fans.

From a practical standpoint, music isn’t like sports, restaurants, or retail. Social distancing guidelines aren’t easily enforceable or even practical in an industry whose primary relationship with consumers—namely touring—is fundamentally based on intimate person-to-person contact, dancing, crowd surfing, and pressing up against the stage. For many artists I spoke with, the idea of touring with fans in face masks separated six feet apart after having their temperatures checked at the gates is antithetical to everything about their business and craft, and why they became musicians in the first place.

“I’ve heard some people talking about this,” says White, “Which to me is counter to the entire premise of the experience of live music. It might work for a golf tournament, but a country show? I personally think that’s a little far fetched. Live music is about being close to people. That’s what it is—it’s real, raw, imperfect, and community driven. But these are unprecedented times. Ultimately we all are asking ourselves right now how far we are willing to stretch the boundaries of what we’re comfortable with to play music live again. ”

GLENMOORE, PENNSYLVANIA – AUGUST 24: Festival-goers enjoy the Citadel Country Spirit USA Festival at … [+] Ludwig’s Corner Horse Show Grounds on August 24, 2019 in Glenmoore, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Lisa Lake/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Re-opening music also has its own unique complications. Unlike restaurants, it’s not just a matter of throwing open the doors, firing up the grills, and letting patrons back in. Many tours are years in the making—a carefully constructed architecture of time, space, dates, design, choreography, and stagecraft. Everyone in Nashville I spoke with agreed that it’s hard enough just to reschedule one tour, for instance if an artist gets sick or injured. The thought of re-constructing all of them a year later has never even been contemplated—because it’s never happened before.

“This is going to take a long time to unravel and figure out,” says Vector’s Levitan. “You can’t just do half a tour. Or pull out a dozen dates in the middle. Or just say, ‘We’re going to kick it downhill to September.” You pull one string here and it starts to unravel everything else. But this is what we do for a living. This is how everyone in the industry feeds their families. We’re all working 12 to 15 hour days. We’ll figure this out because we have to.”

Blackberry Smoke is still waiting to reschedule their 2020 tour.

Courtesy of Blackberry Smoke

Blackberry Smoke’s manager Trey Wilson

Courtesy of Paul Undersinger

It’s been over a month since Blackberry Smoke returned from Canada and cut short their tour. Trey Wilson is still cooped up in his home office, juggling his two kids and still unsure when the band’s tour will resume. Everyone’s still concerned. Music City is still on lockdown.

“It was raining a lot last week,” Wilson tells me when I ask him to describe the mood in Nashville right now. “My wife and kids have been cooped up for so long that I put them in the car and we took a ride downtown. I went my usual route to work, just for the sense of habit and familiarity it provides, but it has been absent for weeks now. My office is on Music Row. Usually the streets and alleys between them are packed with cars, rental scooters, joggers and people who work there, write there, manage there, and produce there. But it was all empty. All the record labels were closed. All the banners with faces and song titles that tout the successes of the artists’ and writers’ recent hits were taken down or tattered blowing in the wind. I took the kids down Demonbreuan and onto Broadway where a few weeks ago, no matter if it was a Monday night or a Thursday afternoon, the honkytonks and bars were packed—doors open so people could see and hear the music coming out of them. But this time, they are all closed. Some had funny signs and some were just pad locked. The kids started complaining that they were hungry, so we headed back home, to shelter back in place.”

NASHVILLE, TN – APRIL 08: A sign is posted on the door of a bar in Downtown Broadway is seen at … [+] night on April 8, 2020 in Nashville, Tennessee. All establishments have been closed due to the coronavirus (COVID-19). (Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Getty Images

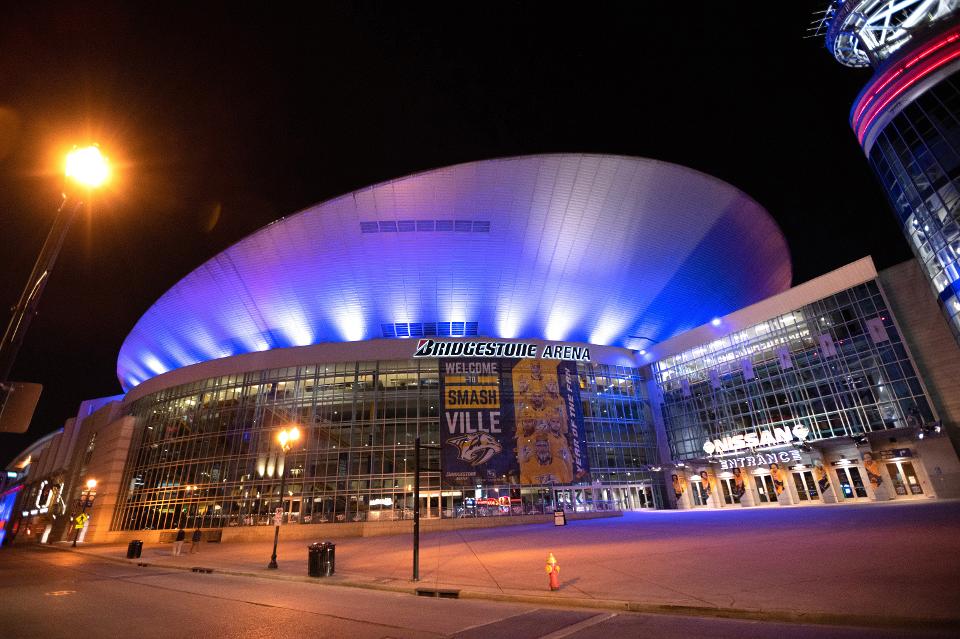

NASHVILLE, TN – APRIL 09: Bridgestone Arena is bathed in blue light on April 09, 2020 in Nashville, … [+] Tennessee. Landmarks and buildings across the nation are displaying blue lights to show support for health care workers and first responders on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Getty Images

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare many things: the inadequacies of our healthcare infrastructure, the economic risks of a biological crisis, how inherently interconnected a global world is, and how much we take our sports and music—and the act of being entertained—for granted.

Everyone likes to talk about “community” these days. But more often than not it’s a throw away word; something that’s wished for rather than something that actually “is”. In Nashville, however, Covid-19 has laid bare how tight Music City really is, and how quickly it rallies around itself.

“Strength and unity—that is what I’m always struck by in our community,” says Essential Broadcast Media’s Joseph Conner. “Don’t forget that coronavirus, the shut-down order, and social distancing in Nashville came directly on the heels of a tornado that rocked Music City and ripped right through East Nashville, killing 24 people and destroying hundreds of homes. We were already rallying around each other before coronavirus hit.”

That same hopeful determination is shared across the Music City at every level of the industry. If there’s one thing coronavirus can’t kill it’s humanity’s love of music. No matter what—or how long it takes—the show will definitely go on.