Black History Month: The sportswomen you should know more about – BBC News

But what about those who came before them? The original GOATs?

To celebrate Black History Month, BBC Sport takes a look at some of the black sportswomen who might not be household names in 2020, but were the trailblazers of the 20th century that smashed boundaries, made history and paved the way for today’s legends.

Some of their stories have been forgotten, and some were probably not told well enough to begin with. Here are seven black sportswomen we think you should know more about.

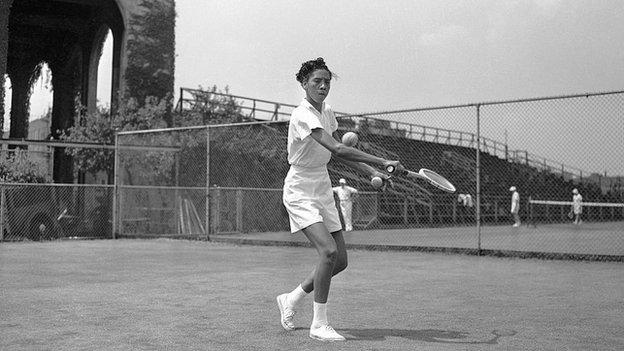

1. Althea Gibson

Althea Gibson was the first black woman to win a Grand Slam tournament in tennis, and in 1957 she became the first black Wimbledon champion.

Gibson was born in 1927 in South Carolina, but her family moved to Harlem, New York, when she was seven years old.

She was raised in an apartment block next to a ‘play street’ (a part of the road blocked off every afternoon) where inner-city kids without access to parks could safely run around and play sport.

Gibson started off playing paddle tennis. By age 12, she was New York City’s women’s champion. An organiser of the play street spotted her talent and took her to the Cosmopolitan Club, a private tennis club for the black middle-classes in Harlem, where she started having tennis lessons.

Racial segregation meant that black players weren’t allowed to compete in the US National Championships, so instead, they formed the American Tennis Association (ATA) and held their own tournament. Gibson won 10 straight ATA national titles between 1947 and 1956.

But in 1950, former US Nationals champion Alice Marble wrote a magazine article questioning why Gibson couldn’t play in the event that would become the US Open.

“The question I’m most frequently expected to answer is whether Althea Gibson will be permitted to play in the nationals this year,” Marble wrote.

“When I directed the question to a committee member of long standing he answered in the negative: ‘Ms Gibson will not be permitted to play and it will be the reluctant duty of the committee to reject her entry.'”

The article sparked more people to speak out and put pressure on the United States Tennis Association, who eventually let Gibson play at the 1950 US National Championships.

A year later in 1951, she was thriving and became the first black woman to play at Wimbledon. And she kept on thriving, winning the 1956 French Championships – to become the first black woman to win one of her sport’s major events.

But 1957 was the biggest year for Gibson. She was now considered the best female tennis player in the world and backed it up by winning Wimbledon, fully cementing her place in the history books. It was such a big deal, that Time magazine, who’d never had a black woman on their cover, put Althea Gibson’s contagious smile on it that August.

In 1958 she defended her Wimbledon title. Not just in the singles either – Gibson had now won three straight doubles titles at The Championships, from 1956-58.

And those US National championships that she was banned from competing at a few years before? She won those in ’57 and ’58 too.

Gibson wasn’t just a tennis legend though. In 1964, she became the first black player to compete on golf’s LPGA tour.

She faced some of the same racist barriers in golf as she had in tennis. Some country club officials refused to allow her to compete, and when she did, she would use her car as a dressing room because so many clubhouses still wouldn’t let black people in them.

In 2019, Katrina Adams, the USTA’s first black president told BBC Sport: “There were many years lost in recognising who she was, what she accomplished, what she overcame.

“But I also think, particularly in America, we weren’t ready to put our African-American players on a pedestal and revere them like we are today.”

Althea Gibson died in 2003 at the age of 76.

Click here if you want to learn more about the pioneering player America forgot.

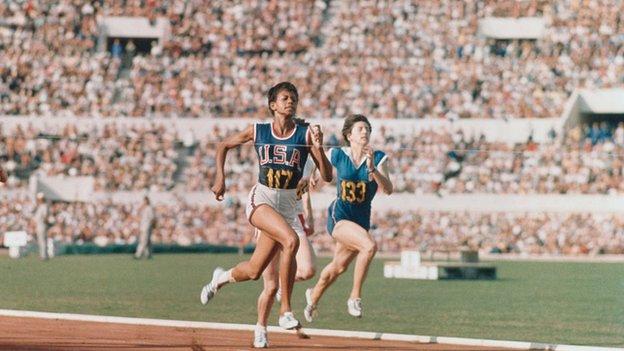

2. Wilma Rudolph

In 1940, Wilma Rudolph was born prematurely in Clarksville, Tennessee, weighing just four-and-a-half pounds. 20 years later, she won three gold medals at a single Olympic Games.

As a child, Rudolph had pneumonia, scarlet fever and polio. The polio caused lasting effects, and she suffered from infantile paralysis when she was five, which meant she couldn’t walk properly for most of her childhood.

Rudolph couldn’t access medical care where she lived because of racial segregation, so instead her mother took her to a historically black medical centre in Nashville called Meharry Medical College.

But that was 50 miles from their home in Clarksville, so every week for two years, Rudolph and her Mum would get the bus to Nashville so she could get treatment for her leg. By the time she was 12, she’d learnt to walk without a leg brace.

But Rudolph didn’t stop at walking… she started competing for her high school track team. When she was in her junior year, she qualified for the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, and at 16 was, the youngest member of Team USA. She won a bronze medal in the 4x400m relay.

During her senior year of high school, Rudolph got pregnant and gave birth to her first child. A few weeks later, she enrolled at Tennessee State University in Nashville, attending the college on a work-study scholarship.

Rudolph won medals at the Pan American Games and four consecutive national championships, plus ran a world-record in the 200m dash that stood for eight years. This was all leading up to the next Olympics in Rome.

At those 1960 Games, the 19-year-old won the 100m, 200m and the 4x100m relay, anchoring her team to a new world record.

She became an international superstar, and she used her popularity to make real change. When she got back home from the Olympics, she insisted that black and white people should be able to mix for her homecoming parade, and they did. It was the first fully integrated public event in Clarksville’s history.

Rudolph retired in 1962 and got a degree. In 1963, she spent time in West Africa as a goodwill ambassador for the US State Department and also attended civil rights marches, protesting against racial segregation in her hometown.

She died at home in Nashville in 1994, aged 54, after being diagnosed with brain and throat cancer a few months earlier.

3. Tessa Sanderson

Tessa Sanderson was born in 1956 in Saint Elizabeth, Jamaica, but grew up in Wolverhampton.

She was the first black British woman to win an Olympic gold medal.

When Sanderson was at secondary school, a teacher noticed her talent and threatened to put her in detention if she didn’t train for athletics. Thankfully for athletics fans everywhere, she started training.

Sanderson went on to win the English Schools finals, and in 1974 she made her senior international debut at the Commonwealth Games, aged 18. She finished fifth, but went on to win three Commonwealth golds later in her career.

And it didn’t matter that she missed out on a medal in 1974, because Sanderson was consistently improving. That year, she broke the junior women’s UK javelin record five times. Two years later, she broke the senior record, throwing 56.14m.

Throughout her career, she shattered that record another nine times, and threw five Commonwealth records too.

But what’s most impressive about Sanderson is how many Olympic Games she competed at. She went to her first in 1976 and her last 20 years later in Atlanta, where she became the second track and field athlete in history to compete at six Olympic Games.

And it was third time lucky for Sanderson, who won Olympic gold at Los Angeles 1984, throwing a new Olympic record of 69.56m. She was Great Britain’s first Olympic champion in a throwing event in the history of the modern Games.

A year after winning the 1986 Commonwealth Games, Sanderson threatened to boycott athletics events after finding out British Athletics were paying her £1,000 per event, while paying £10,000 to her rival Fatima Whitbread, who won gold at 1987 World Championships.

She retired in 1997, but went on to compete in domestic heptathlons. She also worked as a sports reporter for Sky News and was awarded a CBE for her charity work and services to Sport England, after serving as their vice chairman from 1999 to 2005.

A true queen of British sport.

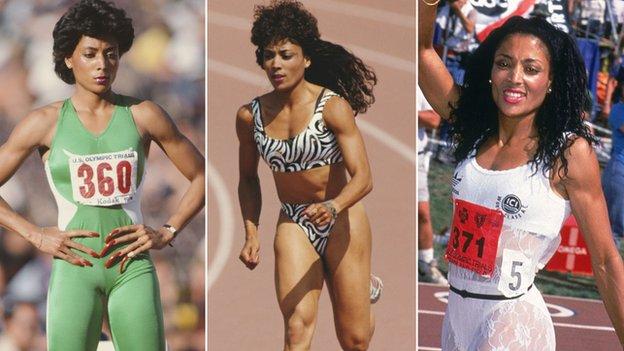

4. Florence Griffith-Joyner

Florence Griffith-Joyner, AKA Flo-Jo, was born in Los Angeles in 1959. She’s the fastest woman of all time, and a track and field icon.

Flo-Jo’s world records of 10.49 seconds in the 100m and 21.34 seconds in the 200m, both set in 1988, have never been broken. To this day, no one has come within even a tenth of a second of 10.49 in the women’s 100m.

At the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Flo-Jo won gold medals in the 100m, 200m and the 4x100m relay. Plus a silver in the 4x400m relay.

And she won various other medals in her career, including 200m silver at the 1984 Los Angeles Games and two World Championships medals.

Throughout her career, people insinuated that Flo-Jo had taken banned substances.

She was running in an era where doping in men’s sprinting dominated the headlines, and people began speculating about her 100m world record of 10.49 seconds at the US Olympic trials in 1988 because it was almost half a second quicker than her personal best, achieved the year before.

She ran the three quickest 100m times in history at those Olympic trials, but a statistician guidebook published by the IAAF (now World Athletics), said the record was “probably, strongly wind-assisted, but recognised as a world record”.

Her times throughout 1988 were consistent, and although she was tested repeatedly, Flo-Jo never tested positive for banned substances.

One thing that’s never been disputed is Flo-Jo’s status as fashion icon on the track.

She wore bold, colourful running suits, was famous for her ‘one-leggers’ and designed some of her outfits herself.

She also had some of the fleekiest nails the track world has ever seen. For the 1988 Olympics, they were six-inches long, painted red, white, blue and fittingly, gold.

Flo-Jo retried suddenly a year after winning the Olympics, causing the drugs rumour mill to go into overdrive. Her husband, Al Joyner, told the BBC’s Sporting Witness that he asked her to retire so they could start a family. Flo-Jo gave birth to a baby girl the following year.

She still worked in sport during her retirement. In 1993, Flo-Jo was asked by former US President Bill Clinton to co-chair his Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. And in 1992, she set up the Florence Griffith-Joyner Foundation to help underprivileged children in sport.

Griffith-Joyner died at just 38 years old in 1998 after suffocating during a seizure in her sleep.

After her death, Clinton said “we were dazzled by her speed, humbled by her talent, and captivated by her style”.

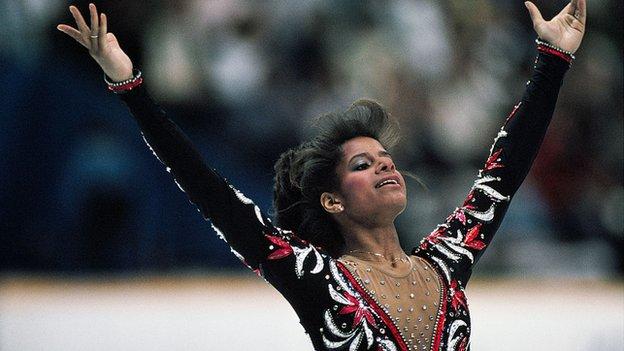

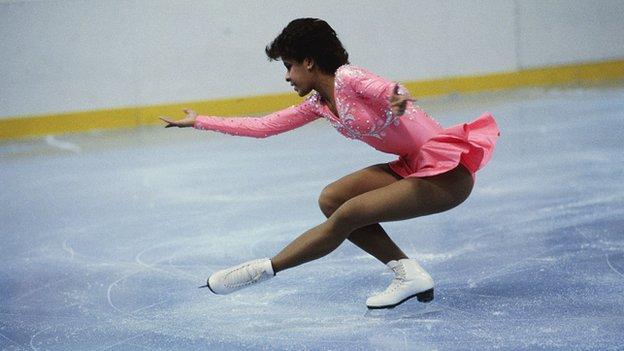

5. Debi Thomas

Debi Thomas was born in 1967 in Poughkeepsie, New York, but grew up in California where she first started figure skating aged five.

She was the first black athlete to win a medal at the Winter Olympics.

Thomas started competing at the age of nine, around the same time her parents divorced. Throughout her career, she spoke a lot about the influence her Mum had on it, and how she used to drive her more than 100 miles a day between home, school and the rink.

When she was in the eighth grade, she finished second at age-group nationals and her coach told her to quit school – which she didn’t. Thomas was from a family who seriously valued education. Her grandfather, the only African-American in his class, got a doctorate in veterinary medicine from Ivy League University Cornell in 1939. Her Mum worked in computer engineering when there were few women in the field, let alone black women.

She won her national title in 1986 and in the same year, went on to win the World Championships, all while studying engineering full time at Stanford University. She was the first athlete since the 1950s to win those titles while studying full-time. That year, she also won ABC’s Wide World of Sports Athlete of the Year award.

In 1987, Thomas finished second at the World Championships despite suffering from Achilles tendinitis in both ankles.

But the following year was the big one – it was the Winter Olympics. Thomas won a bronze medal at the Calgary Games, becoming the first black athlete in history to win a medal at the Winter Olympics.

Since they began in 1924, more than 1000 medals have been won, but only 12 of those have been won by black athletes. Thomas’ win in 1988 was 84 years after the first black athlete won a medal at the summer Games.

Her performance in the Games was remembered because of her fierce rivalry with East Germany’s Katarina Witt. People called it the Battle of the Carmens, because both women skated to the music from an old opera called Carmen, written in 1875.

At the 1988 World Championships, Thomas won a bronze medal and then retired from amateur figure skating, but won the 1988, 1989 and 1991 World Professional Championships.

After graduating in 1991, she started studying at medical school, then had a long career as an orthopaedic surgeon.

Thomas was inducted into the US Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 2000 and was also asked by former US President George W. Bush to be part of the country’s Delegation for the Opening Ceremonies of the Turin Winter Olympics in 2006, along with other Olympians.

In 2015, Oprah Winfrey Network’s television show Fix My Life featured Thomas, looking at the struggles she’s faced in more recent years. Read more about it here.

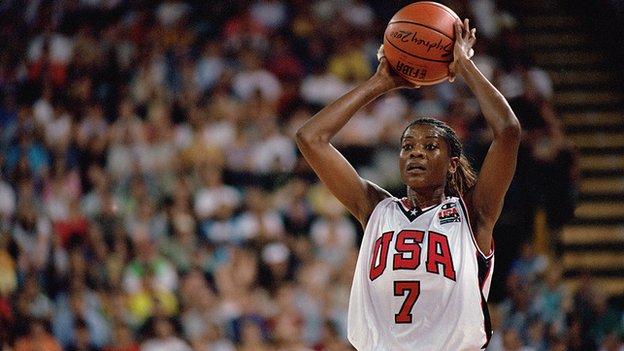

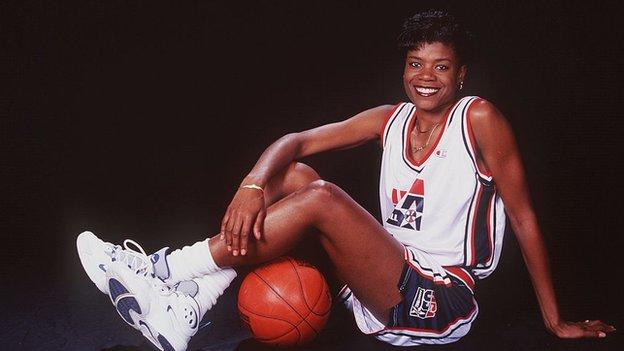

6. Sheryl Swoopes

Sheryl Swoopes, born in Texas in 1971, is a WNBA legend and three-time Olympic champion.

She’s a three-time WNBA MVP and was the first player to be signed in the WNBA. She dominated the courts from then on, winning four straight WNBA titles with the Houston Comets.

In 1995, Nike named a shoe after her, and at that time the only other athlete who had their own signature shoe was Michael Jordan.

Swoopes also won gold medals at three Olympic Games – Atlanta 1996, Sydney 2000 and Athens 2004.

To this day, she still holds the record for points scored in an NCAA championships basketball game. No other player, male or female, has scored more than the 47 points she did in 1993 for Texas Tech.

Swoopes has scored more than 2,000 points with the Houston Comets, and was the second player in WNBA history to be given the regular season MVP award plus the All-Star Game MVP award in the same season.

She led the Comets to victory in the 1997 WNBA Championship just a few weeks after giving birth to her son, who was named after Michael Jordan. Jordan told Swoopes her son would have to be able to dunk if he was going to be named after him.

She also played for the Seattle Storm and the Tulsa Shock. Since retiring from her playing career, Swoopes has worked as a college university coach and analyst.

Swoopes came out as gay in 2005 and spoke publicly about her sexuality, saying it was refreshing that she didn’t have to lie about it anymore. At the time, she was one of the most high-profile athletes in the US to publicly come out as gay.

In 2019, she co-founded a non-profit organisation called Back to Our Roots, which aims to empower and educate young people through sport.

Click here to learn more about Sheryl Swoopes.

7. Derartu Tulu

Derartu Tulu was born 1972 in Bekoji, a town in the highlands of central Ethiopia. The same town, in fact, that three-time Olympic champion Kenenisa Bekele grew up in.

Tulu became Africa’s first black female Olympic champion when she won 10,000m gold at the 1992 Barcelona Games.

Since then, 20 more black African women have become Olympic champions. All of them in athletics.

Tulu made the squad for the Barcelona Olympics when she was 20 years old. The favourite for the 10,000m was Elena Meyer, a white South African woman. Meyer broke away from the pack in the final few laps, and Tulu went with her, eventually winning the race.

She didn’t compete in 1993-94 because of a knee injury, but returned to competition in 1995 at the World Cross Country Championships. She took home the gold medal, despite having being stuck at Athens airport without sleep for 24 hours before the event.

Tulu had a daughter in 1998 but returned to the track and defended her 10,000m Olympics title at Sydney 2000. As if winning wasn’t enough, she smashed through the last 400m of that race in an incredible 60.3 seconds.

No other woman in history had won the 10,000m at two separate Olympic Games. And the only woman who’s done it since Tulu shares the same genes. Her younger cousin, Tirunesh Dibaba – a six-time Olympic medallist and former world-record holder – has become a legend of the sport in her own right.

After winning the World Championships in 2001, Tulu moved onto the roads to compete in marathons, winning in London and Tokyo that year. But she still dabbled in the 10,000m on track, winning a bronze medal at Athens 2004.

In 2009, aged 37, Tulu was still beating the likes of former world record holder Paula Radcliffe to win the New York City Marathon. Since retiring, she’s spent time working as the interim-president of the Ethiopian Athletics Federation in 2018.

If you want to know more about Tulu and that first Olympic gold, watch this.